JoNina Abron-Ervin’s civil rights activism has come full circle.

JoNina Abron-Ervin, ’70, joined the Black Panther Party in 1972 in Detroit, Michigan, and later worked for its headquarters in Oakland, California. Now, she’s teaching the younger generation about activism.

“I’m working with younger activists around the country—virtually—who are trying to organize around the issues affecting their communities,” she said.

A preacher’s kid

Abron-Ervin grew up in Jefferson City, Missouri, where her father was a United Methodist minister.

“I got a discount at Baker for being a preacher’s kid,” she said, laughing. “It was only maybe a couple hundred miles away, and my mother was from Topeka, so we knew the area. My memory of Baldwin City is there was one main street where you’d find most of the stores and everything.”

Abron-Ervin’s roommate for four years was from Kansas City. “By the time I started school, my family had moved away to Iowa so I would only go see them on longer holidays,” she said. “I’d get to go home with my roommate on the weekends, and we had a lot of fun.”

Abron-Ervin recalls a time of social upheaval in the United States while at Baker. She remembers the Black Power movement and opposition to the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War.

“In some ways, there are similarities to today. Baker was a small liberal arts college tucked away in a corner of the country and was somewhat insulated from what was happening in the rest of the world,” she said.

But Abron-Ervin learned from her parents at a young age to stay informed and watch the news. At the time, that included the CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite.

“While it was quiet in Baldwin City, I knew there were things going on in the country. I used to go down to the student lounge to watch the evening news.”

JoNina Abron-Ervin, ’70

Abron-Ervin said a defining experience at Baker came in the summer of 1968 when she and several students and faculty members spent eight weeks in Rhodesia, Africa, which is present day Zimbabwe.

“I didn’t understand a lot about what was going on in Africa,” she said. “The Black people in that country didn’t have control—the white minority had control. Being a part of that trip was a profound experience because I began to learn what was going on in the world.”

While in Rhodesia, Abron-Ervin worked at a Black newspaper. “There, they had censored news publications,” she said. “You would get a newspaper, and it would have these huge white spaces where stories critical of the government had been censored. I celebrated my 20th birthday while there. The trip really educated me about the world and certainly helped me gain understanding, especially to be a journalist. That was a transforming experience.”

How society works

Abron-Ervin was co-editor of the Baker Orange from 1968 to 1970 and graduated in 1970 with a bachelor of arts degree in journalism. Before earning a master of arts degree in communication from Purdue University in 1972, she was the news editor of the Cincinnati Herald.

“I started out wanting to be a political science major,” Abron-Ervin said. “I’ve always been interested in how society works. At some point, I took a journalism class and thought that might be the way to go. If you’re a reporter, you might be assigned to cover some of the major events and have a chance to see them firsthand.”

After working at the Cincinnati Herald, Abron-Ervin moved to Chicago, Illinois, where she was the public relations coordinator at Malcolm X College and later a news reporter at the Chicago Defender, one of the oldest Black newspapers in the United States.

“That newspaper was responsible for a lot of Black people leaving the south and coming to Illinois. I was covering news events and political meetings. I really liked that job because I liked being able to go to events and see what was going on in the community.”

JoNina Abron-Ervin, ’70

Later in Oakland, Abron-Ervin served as the Black Panther newspaper editor and managing editor of the Black Scholar magazine and was active in several social justice organizations from 1974 to 1990. From 1990 until she retired in 2003, she was a journalism professor at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

In the streets

In 2016, Abron-Ervin and her husband, Lorenzo Ervin, moved to Kansas City, Missouri, and help found the Ida B. Wells Coalition Against Racism and Police Brutality. Abron-Ervin said they moved to the area because family lived nearby and they had done political work in 2014 in Kansas City during the Ferguson, Missouri, protests.

“Recently, with the killing of George Floyd and others like Breonna Taylor, we’re seeing again protests and rebellions around the country,” she said. “I think this movement will continue to grow. I fear race relations are worse now than they were back when I was in college and even when I first joined the Black Panther Party.”

One major difference between then and now is social media, Abron-Ervin said. “It changed the culture of not just the U.S. but the world,” she said. “It’s an important tool and a way to let people know about things in a moment’s notice. You can’t minimalize its importance.”

But social media doesn’t replace in-person activism, she said.

“You still have to get out in the streets and do it. Some of us have joked that, ‘Boy, if we had just had Twitter back then.’”

JoNina Abron-Ervin, ’70

The pandemic has kept Abron-Ervin and her husband from attending protests and marches in person lately. “We’re both in our early 70s and are high risk for becoming seriously ill if we contract COVID-19,” she said. “I’m not saying we’ll never go to another protest or march but just not right now because of health dangers.”

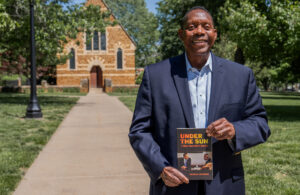

But that won’t keep Abron-Ervin from participating in activism. She’s the author of Driven by the Movement: Activists of the Black Power Era and is working on her autobiography.

“I share my ideas of what’s happening on social media and express my views,” she said. “I’m in close contact with a lot of young activists and helping counsel them. That’s how I’m trying to contribute right now.”

Written by Jenalea Myers, ’08